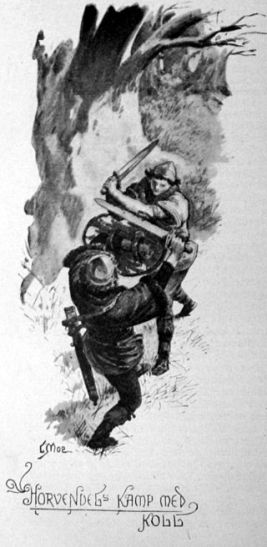

Illustration by Luis Moe from the 1898 edition of The Danish History. “Horwendil, in his too great ardour, became keener to attack his enemy than to defend his own body; and, heedless of his shield, had grasped his sword with both hands; and his boldness did not fail. For by his rain of blows he destroyed Koller’s shield and deprived him of it, and at last hewed off his foot and drove him lifeless to the ground.”

Even in its earliest-known medieval telling, Hamlet’s saga was the story of the long interval between the first motion—the initial impulse or design—and the acting of the dreadful thing. In Saxo the Grammarian’s account, the murder of Amleth’s father Horwendil (the equivalent of Shakespeare’s old King Hamlet) by his envious brother Feng (the equivalent of Claudius) was not a secret. Glossing over “fratricide with a show of righteousness,” the assassin claimed that Horwendil had been cruelly abusing his gentle wife Gerutha. In reality, the ruthless Feng had simply seized both his brother’s kingdom and his wife. No one was prepared to challenge the usurper. The only potential challenger was Horwen- dil’s young son Amleth, for by the time-honored code of this pre-Christian society a son was strictly obliged to avenge his father’s murder.

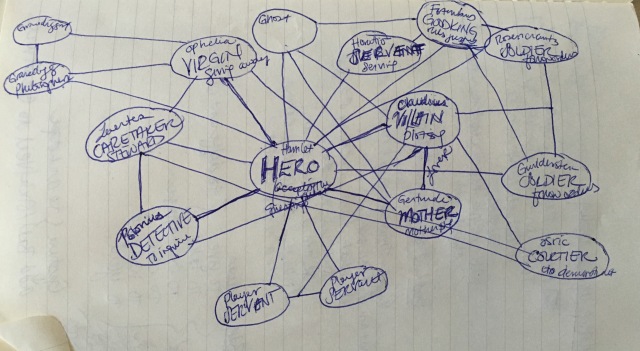

Feng understood this code as well as anyone, so that it was reasonable to expect that he would quickly move to eliminate the future threat. If the boy did not instantly come up with a clever stratagem, his life would be exceedingly brief. In order to grow to adulthood—to survive long enough to be able to exact revenge—Amleth feigned madness, persuading his uncle that he could never pose a danger. Filthy and lethargic, he sat by the fire, aimlessly whittling away at small sticks and turning them into barbed hooks. Though the wary Feng repeatedly used intermediaries (the precursors of Shakespeare’s Ophelia, Rosencrantz, and Guildenstern) to try to discern some hidden sparks of intelligence behind his nephew’s apparent idiocy, Amleth cunningly avoided detection. He bided his time, slipped out of traps, and made secret plans. Mocked as a fool, treated with contempt and derision, he eventually succeeded in burning to death Feng’s entire retinue and in running his uncle through with a sword. He summoned an assembly of nobles, explained why he had done what he had done, and was enthusiastically acclaimed as the new king. “Many could have been seen marvelling how he had concealed so subtle a plan over so long a space of time.”

-Stephen Greenblatt, “The Death of Hamnet and the Maning of Hamlet,” Oct. 21, 2004. New York Book Review.

It is important to note that the tale of Hamlet existed in written form and onstage prior to Shakespeare’s version. It is almost certain that Shakespeare would have had the opportunity to see a version of it and/or read it, possibly from Saxo the Grammarian’s The Danish History.

Hamlet: German boy name, derived from the Old German word for “home.” Also of note: 1. Shakespeare’s 11 year old son, Hamnet, died in 1596, about 5 years before Hamlet was completed. 2. “Amleth” in The Danish History, meaning “foolish or dull,” which speaks to Amleth choosing as a young boy to “play dumb” so his uncle would not see him as a threat until he could revenge his father’s murder.

King Hamlet: Known as “Horwendil” in The Danish History

Ophelia: Derived from Greek οφελος (ophelos) meaning “help”

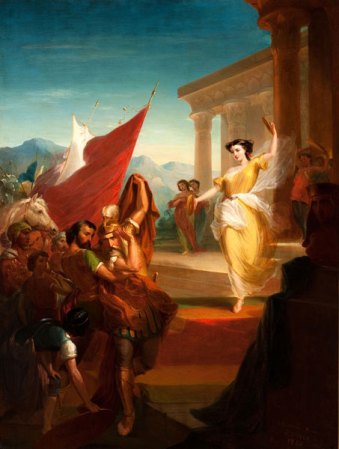

Gertrude: From the Old German name, meaning “strong spear.” Also of note: 1. “Gerutha” in The Danish History. Look at the story of Agrippina the Younger, the 4th wife of the Roman Emperor Claudius.

Fortinbras: “strong arm,” German origin.

Claudius: Most commentators translate the name Claudius with “lame” or “crippled”, but in Latin this name would have sounded just as much as “enclosure” or “safe haven” or even “support” or “one to lean on.” Also of note: 1. “Feng” in The Danish History, a powerful Jutish chieftain. 2. Possibly named Claudius in reference to the Roman Emperor Claudius, who conquered Britain in AD 43. Elizabethans identified him as an archetypal villain. Here is a brief overview.

Laertes: Greek baby name, Father of Odysseus.

Horatio: “time-keeper,” Italian origin.

Rosencrantz: “rosary,” Danish origin.

Guildenstern: “golden star” Danish origin.

Polonius: Latin, relating to Poland. Also of note: 1. From Wikipedia: “In the first quarto of Hamlet, Polonius is named “Corambis”. It has been suggested that this derives “crambe” or “crambo”, derived from a Latin phrase meaning “reheated cabbage”, implying “a boring old man” who spouts trite rehashed ideas. Whether this was the original name of the character or not is debated.” 2. Possibly based on William Cecil, aka Lord Burghley.

Marcellus: Latin, meaning “hammer.”

Francisco: A Spanish variant of the Latin Francis, meaning “Frenchman” or “free one.”

Bernardo: Spanish, “strong as a bear.”

Osric: Anglo-Saxon name, “rich and powerful.”

Voltimand: English name, “courtier.”

Yorick: “earth worker” origin of the name “George”